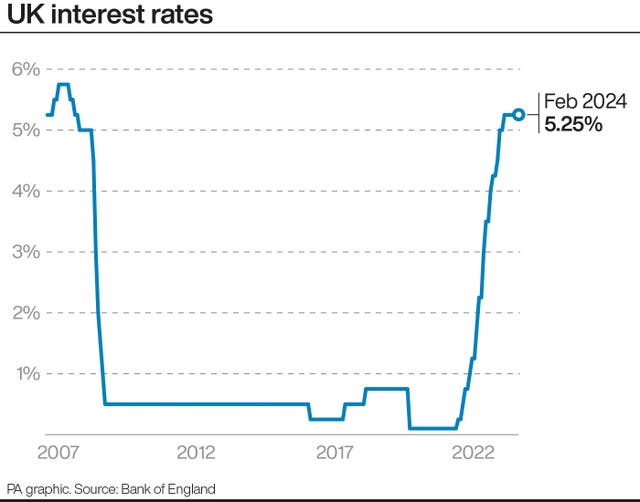

The Bank of England risks pushing the UK into a recession if it holds interest rates where they are now, its own forecasts have shown.

If the Bank’s base rate stays at 5.25%, then gross domestic product (GDP) will fall by 0.2% in the first quarter of this year, and 0.4% in the second quarter.

That would be a recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of contraction in the economy.

If the Bank instead starts cutting rates at the speed that markets had expected before the results of this week’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting were published, GDP will remain unchanged in the first quarter and grow slightly between April and June.

Economists said that it raises questions about when the Bank will start cutting rates. If it does so too late it could lead to claims from politicians and economists that the Bank is hurting the economy.

After the Bank’s report was released on Thursday, it appeared that markets thought it was now less likely that interest rates will be cut in May, but still possible.

“The Bank’s forecast for inflation – largely above the 2% target for much of the forecast horizon – pushes back against those expectations for an early rate cut,” said Chris Turner and Benjamin Schroeder at Dutch bank ING.

“In effect, the Bank is making clear it needs more time and more evidence that the disinflation trend is a true one before it is prepared to firmly step into dovish territory.”

Two members of the Bank’s MPC still voted this week to raise rates, which surprised some analysts.

Meanwhile, Governor Andrew Bailey said that he will need to “see more evidence” that inflation is going to fall to and stay at 2% “before we can lower interest rates”.

“We need to see more evidence that inflation is set to fall all the way to the 2% target, and stay there before we can lower interest rates,” he said.

Martin Beck, chief economic advisor to the EY ITEM Club, said: “The MPC was circumspect on the prospect of rate cuts.

“While today’s statement made a new commitment to ‘keep under review…how long Bank Rate should be maintained at its current level’, it retained previous language that policy will have to stay ‘sufficiently restrictive for sufficiently long’.”

Yet, on the other side, there are indications that cuts will come. For the first time since the early days of the pandemic four years ago, one of the MPC’s members voted to actually cut rates.

Meanwhile, if rates stay at their current levels it will start to push inflation a fair bit lower than the Bank’s 2% target by the end of 2025 and push the economy into a recession.

It is clear therefore, that cuts will need to come at some point to avoid both of these problems, especially as it takes many months for the full impact of rate changes to start having its desired effect.

Yet these cuts are unlikely to be massive. The market is pricing in a cut of around one percentage point – to 4.25% – by the end of this year, the ING experts said.

The Bank said that if rates are cut at the pace that markets expected before Thursday’s announcement, consumer prices index (CPI) inflation will fall to 2.0% by the second quarter of this year.

That would be a year and a half earlier than the Bank expected in November.

But there is a sting in the tail of that forecast. After inflation falls to 2.0% it is expected to rise again, and not come back down until the end of 2026, a whole year later than previously thought.

And Governor Bailey said on Thursday that he is more focused on that later date than the short-term positive news.

“We do expect it to come near to target this spring. And that is, of course, very good news,” he said.

“But we don’t expect that to be the sustained level, it’s going to rise again somewhat thereafter.

“And it’s really that ‘thereafter period’ that we are most focused on when setting policy. We have to look through the short-run impact that energy prices in particular are having.”

House Rules

We do not moderate comments, but we expect readers to adhere to certain rules in the interests of open and accountable debate.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel